-

About Streets

- Introduction

- Defining Streets

-

Shaping Streets

- The Process of Shaping Streets

- Aligning with City and Regional Agendas

- Involving the Right Stakeholders

- Setting a Project Vision

- Communication and Engagement

- Costs and Budgets

- Phasing and Interim Strategies

- Coordination and Project Management

- Implementation and Materials

- Management

- Maintenance

- Institutionalizing Change

- Measuring and Evaluating Streets

-

Street Design Guidance

- Designing Streets for Great Cities

- Designing Streets for Place

-

Designing Streets for People

- Utilities and Infrastructure

- Operational and Management Strategies

- Design Controls

-

Street Transformations

- Streets

-

Intersections

- Intersection Design Strategies

- Intersection Analysis

- Intersection Redesign

- Mini Roundabout

- Small Raised Intersection

- Neighborhood Gateway Intersection

- Intersection of Two-Way and One-Way Streets

- Major Intersection: Reclaiming the Corners

- Major Intersection: Squaring the Circle

- Major Intersection: Cycle Protection

- Complex Intersection: Adding Public Plazas

- Complex Intersection: Improving Traffic Circles

- Complex Intersection: Increasing Permeability

- Resources

Global Street Design Guide

-

About Streets

- Introduction

- Defining Streets

-

Shaping Streets

Back Shaping Streets

- The Process of Shaping Streets

- Aligning with City and Regional Agendas

- Involving the Right Stakeholders

- Setting a Project Vision

- Communication and Engagement

- Costs and Budgets

- Phasing and Interim Strategies

- Coordination and Project Management

- Implementation and Materials

- Management

- Maintenance

- Institutionalizing Change

-

Measuring and Evaluating Streets

Back Measuring and Evaluating Streets

-

Street Design Guidance

-

Designing Streets for Great Cities

Back Designing Streets for Great Cities

-

Designing Streets for Place

Back Designing Streets for Place

-

Designing Streets for People

Back Designing Streets for People

- Comparing Street Users

- A Variety of Street Users

-

Designing for Pedestrians

Back Designing for Pedestrians

- Designing for Cyclists

-

Designing for Transit Riders

Back Designing for Transit Riders

- Overview

- Transit Networks

- Transit Toolbox

-

Transit Facilities

Back Transit Facilities

-

Transit Stops

Back Transit Stops

-

Additional Guidance

Back Additional Guidance

-

Designing for Motorists

Back Designing for Motorists

-

Designing for Freight and Service Operators

Back Designing for Freight and Service Operators

-

Designing for People Doing Business

Back Designing for People Doing Business

-

Utilities and Infrastructure

Back Utilities and Infrastructure

- Utilities

-

Green Infrastructure and Stormwater Management

Back Green Infrastructure and Stormwater Management

-

Lighting and Technology

Back Lighting and Technology

-

Operational and Management Strategies

Back Operational and Management Strategies

- Design Controls

-

Street Transformations

-

Streets

Back Streets

- Street Design Strategies

- Street Typologies

-

Pedestrian-Priority Spaces

Back Pedestrian-Priority Spaces

-

Pedestrian-Only Streets

Back Pedestrian-Only Streets

-

Laneways and Alleys

Back Laneways and Alleys

- Parklets

-

Pedestrian Plazas

Back Pedestrian Plazas

-

Pedestrian-Only Streets

-

Shared Streets

Back Shared Streets

-

Commercial Shared Streets

Back Commercial Shared Streets

-

Residential Shared Streets

Back Residential Shared Streets

-

Commercial Shared Streets

-

Neighborhood Streets

Back Neighborhood Streets

-

Residential Streets

Back Residential Streets

-

Neighborhood Main Streets

Back Neighborhood Main Streets

-

Residential Streets

-

Avenues and Boulevards

Back Avenues and Boulevards

-

Central One-Way Streets

Back Central One-Way Streets

-

Central Two-Way Streets

Back Central Two-Way Streets

- Transit Streets

-

Large Streets with Transit

Back Large Streets with Transit

- Grand Streets

-

Central One-Way Streets

-

Special Conditions

Back Special Conditions

-

Elevated Structure Improvement

Back Elevated Structure Improvement

-

Elevated Structure Removal

Back Elevated Structure Removal

-

Streets to Streams

Back Streets to Streams

-

Temporary Street Closures

Back Temporary Street Closures

-

Post-Industrial Revitalization

Back Post-Industrial Revitalization

-

Waterfront and Parkside Streets

Back Waterfront and Parkside Streets

-

Historic Streets

Back Historic Streets

-

Elevated Structure Improvement

-

Streets in Informal Areas

Back Streets in Informal Areas

-

Intersections

Back Intersections

- Intersection Design Strategies

- Intersection Analysis

- Intersection Redesign

- Mini Roundabout

- Small Raised Intersection

- Neighborhood Gateway Intersection

- Intersection of Two-Way and One-Way Streets

- Major Intersection: Reclaiming the Corners

- Major Intersection: Squaring the Circle

- Major Intersection: Cycle Protection

- Complex Intersection: Adding Public Plazas

- Complex Intersection: Improving Traffic Circles

- Complex Intersection: Increasing Permeability

- Resources

- Guides & Publications

- Global Street Design Guide

- Designing Streets for People

- Designing for Cyclists

- Overview

Overview

Encouraging cycling as an efficient and attractive mode of transportation requires the provision of safe and continuous facilities. Cycling is a healthy, affordable, equitable, and sustainable mode of transportation, with positive impacts on congestion and road safety. Cities that invested in cycling have seen congestion levels decline and streets become safer for all users.1

Cycling is also good for the economy. Many recent studies demonstrate the impact of cycling on local economies. Cities that increase the cycle accessibility of their business centers attract new customers, generating more spending in local stores, and ultimately creating jobs and tax revenues. Infrastructure and design can make cycling a popular activity, appealing to a wide range of potential riders.

While cyclists can share the road with motor vehicles on quiet streets with low speeds, navigating larger streets and intersections requires dedicated facilities. Design safe and comprehensive cycle networks for cyclists of all ages and abilities. If cycling is not a safe option, potential cyclists may decide not to ride.

High-volume corridors should provide wider cycle facilities to carry larger volumes. Creating a bikeable city requires secure cycle parking spaces, easy access to transit, and a cycle share system.

Cycle lanes and tracks should allow for social and conversational riding for everyday use as well as long commutes. They should be designed for all types of riders and all levels of comfort, from the 5-year-old to the 95-year-old cyclist.

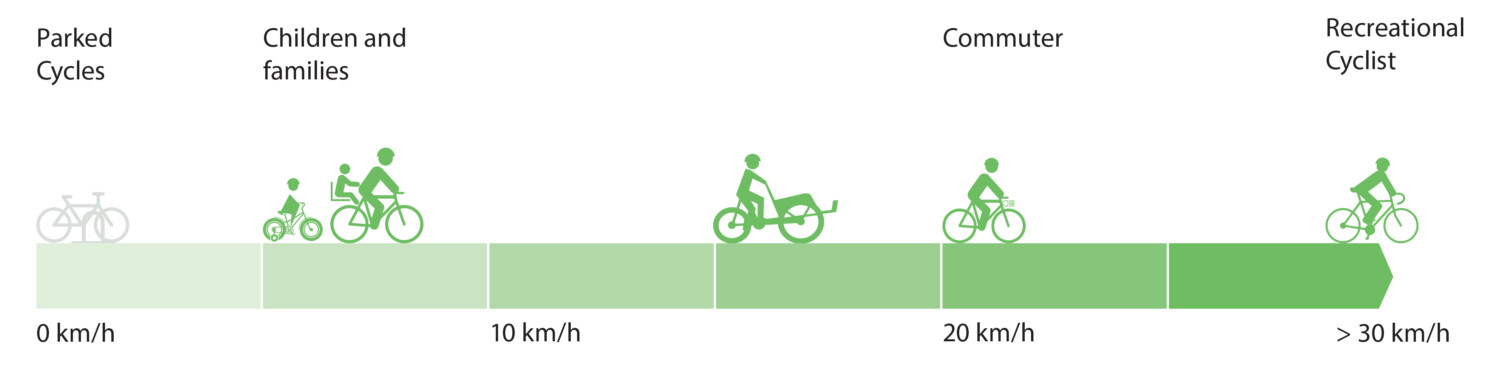

Speed

Cyclists ride at different speeds depending on their purpose, the length of their total route, their confidence level, and the facility they are using. Young children will ride at a slower speed than a cyclist making a delivery, and visitors will ride differently from locals and commuters. Design cycle facilities to accommodate riders at various speeds. Provide

sufficient protection from travel lanes, taking into account speed differentials and vehicle volume.

Electric cycles that travel up to 20 km/h often share facilities with other cycles. Design wider cycle lanes along high-volume corridors to allow fast riders to pass slower riders.

Variations

Cycle facilities should be designed for diverse vehicles and riders, for children on small tricycles, and people carrying goods in big cargo bikes, as well as cycle-rickshaws and pedicabs.

Conventional Bicycles

The most common non-motorized, single-track vehicle.

Tricycles, Cycle-Rickshaws, and Pedicabs

Tricycles such as pedicabs and cycle-rickshaws are wider, and in some cases share cycle lane facilities. They typically carry one to two passengers.

Cargo Bikes and Cycle Trucks

Cargo bikes are human-powered vehicles specifically designed for transporting loads. A cargo bike may have different forms and dimensions and can be either a bicycle or a tricycle.

Electric Cycles or E-bikes

These are cycles with electric engines.

Levels of Comfort

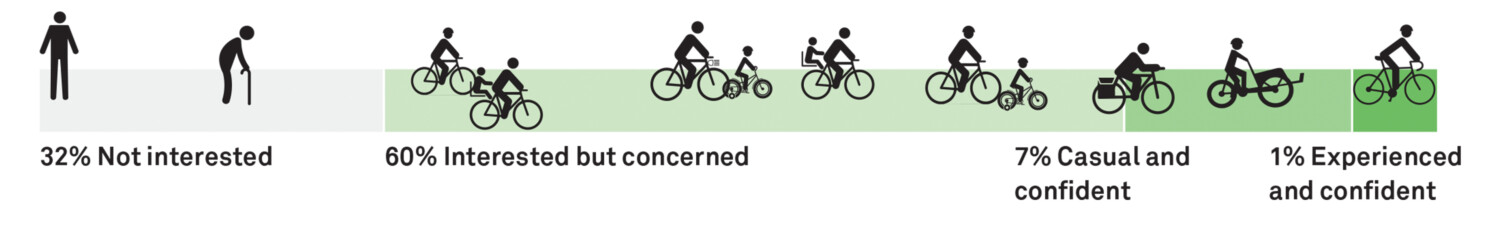

Many people are interested in cycling but are dissuaded by stressful interactions with motor vehicles. These potential cyclists, defined as “interested but concerned,” account for a majority of the population and vary by age and cycling ability.2 Experienced and casual cyclists are more traffic tolerant, but they account for a significantly smaller share of the population.

Cycle facilities should be designed not only for the highly capable and experienced cyclist, but also and especially for young children learning to ride, for senior riders, adults carrying children or freight, and workers commuting long distances. These riders need higher degrees of separation and protection from motor vehicle traffic.

Footnotes

1. Flusche Darren, Bicycling Means Business – The Economic Benefits of Bicycle Infrastructure. Advocacy Advance. New York City Department of Transportation. Measuring the Street: New Metrics for 21st Century Streets (New York, NY: NYC DOT, 2012).

Rachel Aldred, Benefits of Investing in Cycling (Manchester: British Cycling, 2014).

2. Geller Roger, “Four Types of Cyclists,” Portland Office of Transportation, 2015, accessed June 7, 2016, ttps://www.portlandoregon.gov/transportation/article/264746.

Adapted by Global Street Design Guide published by Island Press.

Next Section —